Prefix and Postfix Increment Deep Dive

Recently a read a blog post by Eric Lippert about the top ten things he wished had been designed differently for C#. If you have not read it, you can find it here. It is worth reading in its entirety. The section that got me thinking was “#3: I rate plus-plus a minus-minus”. In it, he makes some very solid points about his dislike of the increment and decrement operators. Firstly he points out that the increment operator can easily be replaced with “x += 1;”. More importantly, he shows that the increment operator has two purposes, to return a value and alter the value of the variable. So by it’s very definition, the expression has a side effect.

But the following statement is the one that grabbed my attention.

Next, almost no one can give you a precise and accurate description of the difference between prefix and postfix forms of the operators. The most common incorrect description I hear is this: “The prefix form does the increment, assigns to storage, and then produces the value; the postfix form produces the value and then does the increment and assignment later.”

This explanation, that Lippert is saying is wrong, is the exact way that I was taught that it worked. Granted, I was taught originally in C++, and this may be true for how C++ works. I have always assumed that C# worked the same way. Lippert is saying that my assumption is wrong.

He goes on to describe what it really does.

Why is this description wrong? Because it implies an order of events in time that is not at all what C# actually does. When the operand is a variable, this is the actual behavior:

- Both operators determine the value of the variable.

- Both operators determine what value will be assigned back to storage.

- Both operators assign the new value to storage.

- The postfix operator produces the original value, and the prefix operator produces the assigned value.

So what he is saying is that both the increment and decrement operators do the arithmetic first and later return the value. But I was not satisfied with the text description, I wanted to know how it really worked. I wanted to see how it worked in IL. So I wrote the following code.

The first method does some simple addition. It serves as a benchmark for understanding what is happening in the IL. The next two methods exercise the prefix and postfix unary increment operators respectively and assign the resulting value a different variable.

##Understanding IL##

In order to understand what is happening when the code executes, you need to understand a little about how IL works. IL, or intermediate language, is the language that C# is compiled to and the language that the CLR executes. So it is analogous to an assembly language for a virtual machine.

IL is a stack based language. In order to do any operations or assignments, values must be moved from registers to the stack. Addition is done on the stack. Assignment is done by pushing a value onto the stack and then popping it off the stack into a different variable. I admit I am not an IL expert. Much of what I know about IL comes from this Wikipedia page.

So I took the code I wrote, listed above, and compiled it in Visual Studio. Then I used Telerik’s Just Decompile to view the IL it generated. It is important to note here that I compiled the code in the Debug configuration so that no compiler optimizations would be used. If I had compiled in the Release configuration, these methods would have been optimized down to a single returned value.

##Examining the Code##

Let’s start by looking at the method that uses the long hand way to increment a number.

Lines 3 - 6 allocate space for the variables. Lines 10 and 11 perform the assignment into the “a” variable by pushing 10 onto the stack and then popping it off the stack into “a”. Lines 12 - 14 perform the addition by pushing “a” and 1 onto the stack and then adding them. Line 15 pops the sum off the stack into “b”. Lines 16 - 21 return the value from “b”.

The code illustrates how the stack is used in IL to assign values and perform arithmetic. The code is not equivalent to using a unary increment operator because the value of “a” is not altered. So let’s look at the code that uses the prefix form of the increment operator.

Lines 11 - 16 perform the addition. But the result is not stored in “b”, the result is stored in a temporary variable named “V_2”. Lines 17 - 20 assign the value from “V_2” into “a” and “b”. This illustrates where my misunderstanding came from. I assumed the assignment into “b” was done directly from “a”, but it is not.

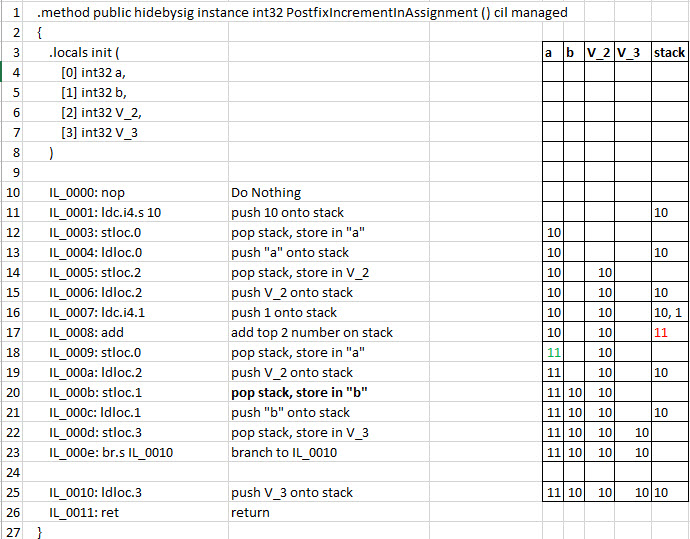

Here is the code for the postfix form of the operator.

Lines 11 - 14 store the value ten into “a” and “V_2”. Lines 15 - 18 perform the addition and store the result into “a”. Lines 19 - 20 assign the value from “V_2” into “b”.

##Conclusion##

I think I understand what Lippert said about the common explanation being wrong. Because I assumed that “b” would be assigned from “a” for both forms of the operator, I made assumptions about when the calculation was done. Seeing how the intermediate variable is used makes it clear that the arithmetic is always done first. The real difference comes from whether or not the intermediate variable has the value from before the addition or after.

Postscript

I am sure some people will point out that these details are unimportant and they will generally be right. The IL code does what I thought it does, just now how I thought it did it. And as I said, if compiler optimizations are on, none of this is likely to matter. I wrote this to satisfy my curiosity, not to improve the performance of my code.

Comments Section

Feel free to comment on the post but keep it clean and on topic.

comments powered by DisqusAbout Me

![]() My name is Eric Potter. I have an amazing wife and 5 wonderful children. I am a Microsoft MVP for Developer Tools and Technologies, the Director of Technical Education for Sweetwater in Ft. Wayne Indiana, and an adjunct professor for Indiana Tech. I am a humble toolsmith.

My name is Eric Potter. I have an amazing wife and 5 wonderful children. I am a Microsoft MVP for Developer Tools and Technologies, the Director of Technical Education for Sweetwater in Ft. Wayne Indiana, and an adjunct professor for Indiana Tech. I am a humble toolsmith.

pottereric.github.com